Thoughts on lists, trees, and other data structures

This past spring, I used to go to a study room in Clemons after dinner to work on problem sets. Those rooms have white boards, which I often used to check over work or write some notes as I did my homework. After I was done with my homework, I’d start drawing trees and come up with rotation algorithms. Sure, there are algorithms out there for balanced trees, but I always got the feeling that they were really generic and hard to improve.

(From Wikipedia)

(From Wikipedia)

That image represents a red-black tree, which is a self-balancing tree. A red-black tree balances itself after every insert, which is done by rotations. Looking at a picture of a tree rotation makes it a lot simpler to understand. It’s important to balance a tree and minimize its overall height to maximize the search efficiency.

I thought rebalancing a tree was too computationally expensive. If you had to do it after every insert, it seems like you’d really slow things down. What if you didn’t rebalance after every insert? If you inserted values sequentially without rebalancing after every insert, you’d just have a linked list, right?

I think I then started to think about how to turn a linked list into a balanced tree. I forget where that took me :). I did come up with a tree that you can balance on-demand (on GitHub). I don’t remember whether or not it works! Even if it does, it’s probably very inefficient. I think part of it started off as a napkin doodle. Anyway, at the very least, it helped me learn more about Go.

Over the summer, a close friend told me about skip lists:

Skip lists are essentially layered linked lists. The higher levels are “fast lanes,” which allow you to skip nodes. Here’s the great thing about skip lists: they have the same average time complexity of balanced binary search trees (O(log n)), and they don’t require balancing! That’s perfect!

What’s the point?

I’ve come to realize that if you’re going to build a database, you need to make sure you pick the right data structures. When I started thinking about this stuff last March, I think I assumed that once I pick a couple of things that seemed to work, everything else would fall into place. I slowly learned otherwise.

Inspiration from Datomic

Earlier this month, Craig Andera (@craigandera) came to talk about Datomic. Craig mentioned how Datomic is centered around time and facts. In the Datomic world, a database has facts and, and if something is a fact at a certain point in time, it always stays a fact. But facts might not be facts later on in time, or previously in time.

What I really liked about Datomic was that you can look at the data (or facts!) which exist right now, but you can also go back in time to see what was there before. You can observe the state of the database in the past. That’s cool!

Persistent data structures

I think it’s sort of interesting how databases seem to take on the characteristics of what they’re developed in. Datomic is written in Clojure, and Craig mentioned several times how certain parts of Datomic are like parts of Clojure.

Clojure’s a functional language, and (please correct me if I’m wrong!) I think functional languages are based around immutable data types. If you have a tree, for example, and you append something to it, you’d get a completely new tree. The old tree never changes. It’s persistent.

Internally, Datomic uses an append-only, persistent tree. Neat!

Lexicon, an ordered list, and a fickle key-value store

Writing a database is a hard task, so I had to break it down into smaller ones. A few months ago, I decided I really had to get down to the core of this thing and build it up from the ground up just as I want it.

I created lexicon, which is an ordered key-value map package for Go. Lexicon uses another package I wrote, which essentially added ordering to the container/list package that’s in Go’s standard library. I kept it simple enough to not be restrictive, yet still very useful.

After I had a decent version of lexicon, it didn’t take long to write a simple TCP server wrapper around it and have a very basic key-value store. I think at that point, I thought: whoa… that was easy! I think I was able to get replication working (well, trivial replication) in one sitting.

It gets complicated.

Eventually, I started thinking about how I could keep replication safe. Originally, a “primary” would just broadcast the commands its got to its replicas, but that’s not safe. What if a replica shuts down? How do we know that the replica is at the same state at the primary?

Another issue was that I wanted to add some form of transactions. I wanted to be able to put in transactional logic. Hmm… oh! I like how CouchDB has multiversion concurrency control using revisions for each document. Maybe I could have a version for each key!

These two problems seemed rather orthogonal. I couldn’t figure out a single solution for both of them. I think at this point, I just stopped working on this.

And then I heard about Datomic.

That’s it! I don’t need versions for each key, but rather versions for the entire database! That way I could if transactions are operating against an old version, and I could keep replicas synchronized by comparing versions! Now, how do I add versions to this database thing? That’s when things got tough.

An easy way to store versions is to make raw copies. That’s not efficient by any means! That would be a waste of a lot of space. The answer seemed to be a persistent data structure. Somehow I stumbled onto treaps, and found a persistent treap package for Go. It didn’t take long before I had versions supported in lexicon.

The issue with treaps

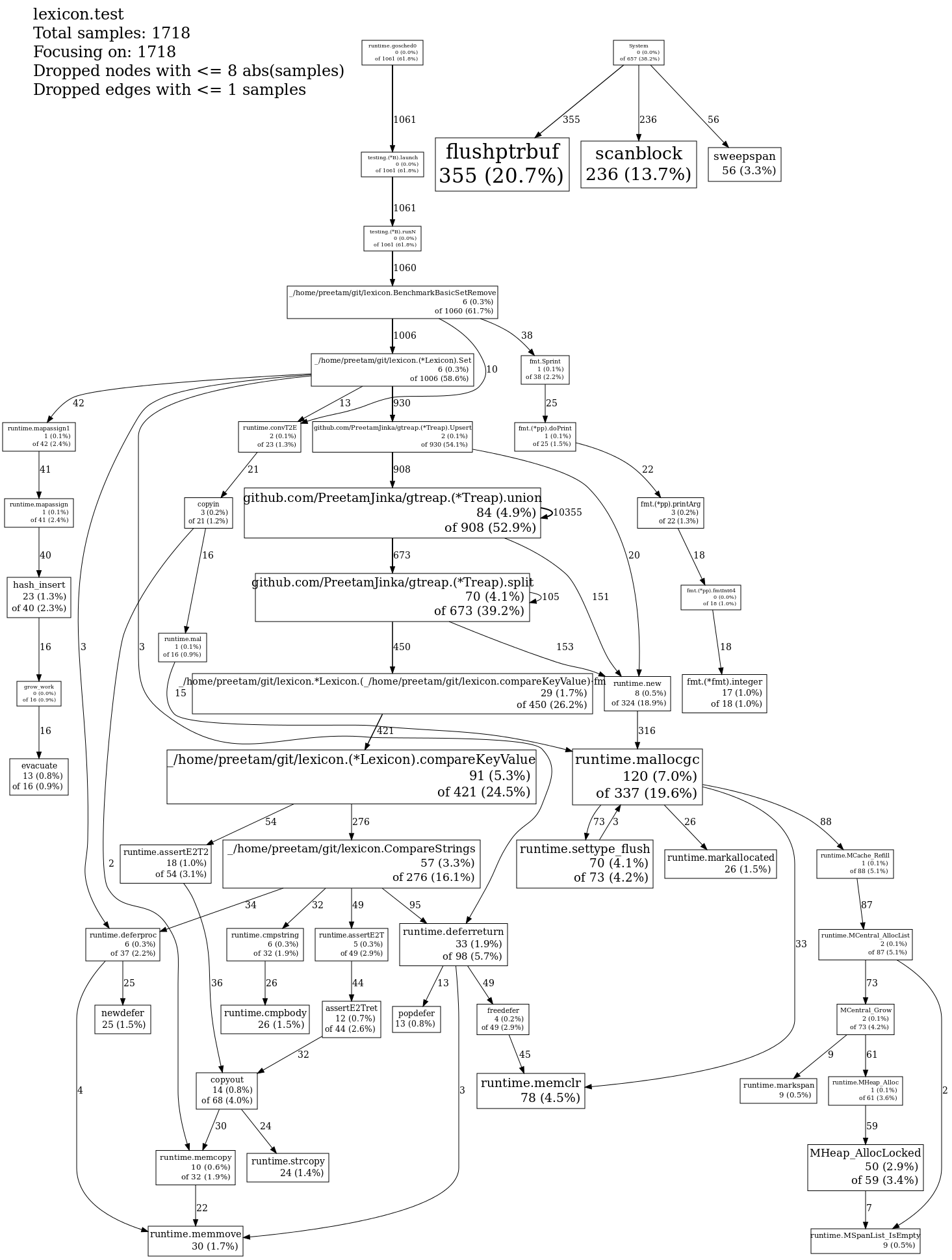

The most important issue that I’ve noticed with my versioned treap stuff was that it’s incredibly memory-hungry. It just seemed to have such a massive overhead. Oh and, of course, a treap is a tree. There’s rebalancing. It’s relatively expensive.

I had to get rid of the treaps! I needed a new data structure. A versioned skip list! I tried to find a persistent skip list, but then stumbled onto this comment on Stack Overflow:

The property of skip lists that makes them good for concurrent updates (namely that most additions and subtractions are local) also makes them bad for immutability (namely that a lot of earlier items in the list point eventually to the later items, and would have to be changed). […] Thus, tree structures are better for immutability (as the damage is always locally limited–just the node you care about and its direct parents up through the root of the tree).

Argh. Okay, so I have to make it mutable, since I’d like to make this write-intensive. I tried to look for a mutable, versioned skip list. I couldn’t find one…

Writing a list

My sister: What are you doing?

Me: Making a list.

My sister: And checking it twice?

Me: -_-

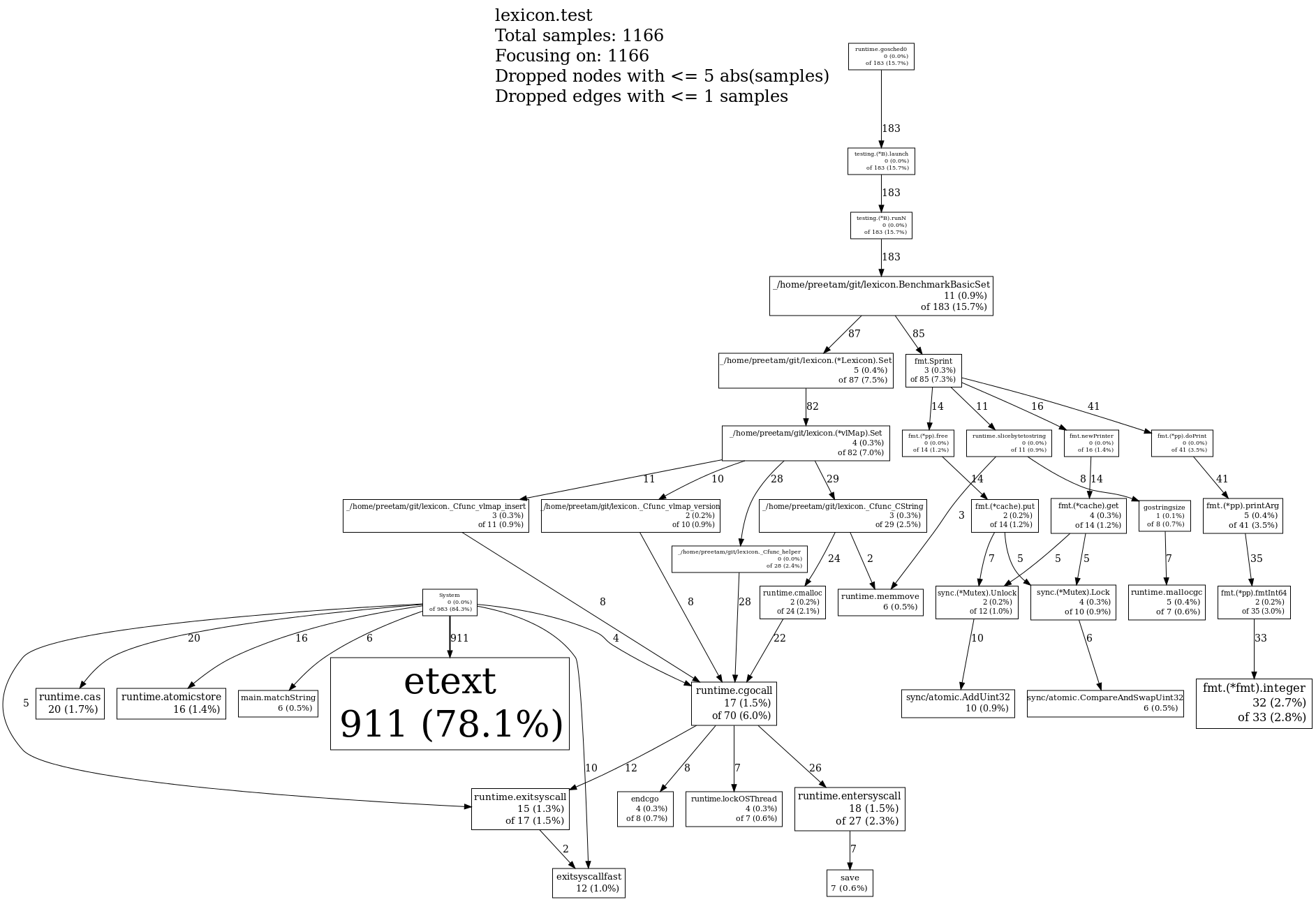

This past week, I wrote vlmap, which is a versioned, ordered skip list map written in C. Lots of words, but what do they mean?

It’s ordered. The keys are stored in order (lexicographically), so it’s possible to do range reads over the data structure.

It’s versioned. I can see what the list looked like in the past. This means I can do snapshot reads!

It’s a map, so it’s an associative array.

It’s written in C. I think I chose to write it in C because I got pissed at Go’s garbage collector while I was testing out the treaps :P. This was actually very significant. I spent a few days working with Valgrind to make sure I wasn’t leaking any memory. I think this was my first big C project, so I definitely learned a few things along the way. Besides that, since it’s written in C, I can reuse it in many languages, including Go. In fact, the primary test for it right now is written in Go.

I’m really, really proud of this vlmap project. I think it’s incredibly neat to have a versioned data structure. You can even iterate through a snapshot! That’s awesome!

Speed

A skip list is much, much better. Not only is it faster, it also uses significantly less memory. I have a couple of pprof-generated profiles below. Using only inserts, I got… 17043 ns/operation for a treap, 3911 ns / operation for a skip list.

Final thoughts

I think this has been my longest blog post so far… and I’m making it even longer right now! I learned a lot over these past few days, weeks, and months. I hope you learned a thing or two from this blog post as well. There’s still a lot out there to learn. Lock-free algorithms and thread-safety are probably what I’m going to look at next, but I’m also going to think about the next big challenge for this database I’m building.

I don’t have a comment system, but if you have a question or a comment, hit me up on Twitter (@PreetamJinka)!