Caching and crashing in lm2

Background

lm2 is my ordered key-value storage library. You can read my post about it here. There’s a lot to say about this little library, so this will be the first of a few posts about how lm2 works and why I chose to do things a certain way.

Caching

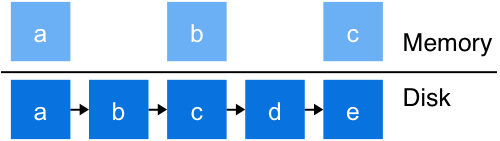

lm2 is essentially a linked list on disk. Everyone knows linked lists aren’t very fast. Searches take a ridiculously long time and require a lot of seeking. That’s why lm2 has a record cache, which stores a subset of the key-value records in memory. This cache really speeds up searches, but it’s used for much more. It’s also used for the write path. All writes in lm2 happen in memory before they’re durably recorded to disk.

There is only one level of caching at the moment. If you think about it, the architecture looks like a 2-level skip list.

A cache like this has some interesting behavior when you have large scans over many records.

Scan resistance

Scan resistance is about keeping the cache “good” when faced with large scans. A scan will access lots of elements, but many will not be accessed again. For example, an LRU is a bad choice for scans because it will insert every accessed element, but many won’t be accessed again.

lm2 uses probability to insert elements into the cache. Like a skip list, records are probabilistically inserted into the record cache whenever they’re accessed. A frequently accessed record may not be in the cache, but it’s definitely more likely. Rarely accessed elements will rarely make it into the cache.

This approach is scan resistant because a single, full collection scan won’t destroy the cache. The other benefit is that cached records tend to be at the areas that are read the most, which I think is what you want from a cache like this.

The bad thing about using a probabilistic cache is that it can take a while for it to “warm up.” We’ll get back to this later.

No dirty records

Besides the time during a write, lm2 does not hold dirty records. This means that the cache has records as they appear on disk. This makes it really easy to evict elements because there isn’t any flushing to do.

Crashing

The fact that lm2 is append-only and does not overwrite records only applies to some data, like the actual keys and values. There’s a bunch of metadata (pointers, versions, tombstone versions, etc.) that is updated in-place. As I mentioned earlier, all of these updates first happen in memory.

Some systems (like InnoDB) use rollback information to undo changes that happen in place. This doesn’t exist in lm2. Once something changes, there’s no going back. But what if something bad happens halfway (or some other arbitrary point) into a write? This is undefined. So what do you do? Crash!

Crashing isn’t a big deal in lm2. Writes are guaranteed to be fully durable when acknowledged, so partially written data is cleanly discarded. The in-memory state is always thrown out. This includes the cache (which takes a while to build!).

Early on during testing, I realized that recovery after losing the cache was horrible. This is where the poor performance of a linked list really shows. To counteract this effect, lm2 now periodically saves the cache state in the background. Every few seconds, it writes the offsets of the records in memory to a separate file. After a crash, it reads these records back into memory and is able to perform just as well as it did before the crash.

Further reading

For more on scan resistance, check out this page titled “Making the Buffer Pool Scan Resistant” in the MySQL reference manual.

Also see “Saving and Restoring the Buffer Pool State”. This is where I got the record cache saving idea :).